Many questions test the concept of conditional probability via Bayes’ Rule. The results may be counter-intuitive, which can normally be attributed to base rate fallacy.

This post summarizes some commonly used techniques to solve such problems. Then, we will illustrate the method using a few well-known textbook examples. After reading this post, one should be able to easily tackle a widely covered class of questions. As a teaser, we state one example question below

In a machine learning classification procedure, each observation is classified as either 0 or 1. Suppose you have deployed a model with recall 90% and false discovery rate 5%. Furthermore, assume you estimate the population prevalence of 0’s to be 90% and hence 1’s 10%. What is the probability that a new observation is of label 1, given that your classifier says it was?

The answer? Not that high.

Methodology

Before diving into the solution, let’s prepare some ingredients first.

Conditional Probability

Let \(A\) and \(B\) denote two events with the unconditional probability of \(B\) being greater than zero, i.e. \(\mathbb{P}(B) > 0\). The conditional probability of \(A\) given \(B\) is defined as \[ \mathbb{P}(A | B) \stackrel{\text{def}}{=} \frac{ \mathbb{P}(A, B) }{ \mathbb{P}(B) } \] where \(\mathbb{P}(A, B)\) denotes the probability that both \(A\) and \(B\) occur. This representation is sometimes written alternatively as \[ \mathbb{P}(A, B) = \mathbb{P}(A | B) \mathbb{P}(B) \] One should note that the order of \(A\) and \(B\) matters in the above equations.

Bayes’ Rule

The Bayes’ Rule connects two closely related conditional probabilities \(\mathbb{P}(A | B)\) and \(\mathbb{P}(B | A)\) via the equation below \[ \mathbb{P}(A | B) = \frac{ \mathbb{P}(B | A) \mathbb{P}(A) }{ \mathbb{P}(B) } \] provided that \(\mathbb{P}(B) > 0\). Though named after Thomas Bayes, this theorem holds true as a fundamental law in probability theory regardless of Bayesian or frequentist’s views. This is because one can prove this theorem simply by using the definition of conditional probability. Nonetheless, Bayesian interpretation are often quoted in this context: If we consider \(A\) as some parameter that describe real-world configurations and \(B\) as some data or evidence that we collected, then re-write the above formula as \[ \mathbb{P}(A | B) \propto \mathbb{P}(A) \] We can interpret it as, using Wikipedia’s words, that

The theorem expresses how a degree of belief, expressed as a probability, should rationally change to account for availability of related evidence.

Law of Total Probability

Following the above interpretation, \(\mathbb{P}(A)\) can be thought of as some prior information of the parameters of interest while \(\mathbb{P}(B)\) is the unconditional probability of data yet to be observed. However, \(\mathbb{P}(B)\) cannot be determined a priori, therefore, we will need the Law of Total Probability to calculate it. We state the law in its original form below and then later show how we will apply it. Let \(\{H_i\}_{i}\) be a partition of the sample space, in other words

- Each element is non-empty (\(H_i \neq \emptyset\)), and

- The union of the collection of hypotheses, \(\cup_i H_i\), covers the entire sample space, and

- Any pairwise intersection is empty (i.e. \(H_i \cap H_j = \emptyset\), a.k.a. pairwise disjoint)

If you prefer fancy consulting terms, this is also known as the MECE principle, i.e.

Mutually Exclusive and Collectively Exhaustive

With partition \(\{H_i\}_{i}\), we can express the probability of any event \(A\) as \[ \mathbb{P}(A) = \sum_{i} \mathbb{P}(A | H_i) \mathbb{P}(H_i) \]

The Solution

We will re-state the original problem in a broader context. Consider a problem of hard classification where the sample space can be partitioned into collection \(\{S_i\}_i\). Our goal is to determine whether a subject is in some particular set \(S_j\). Suppose we also have a classifier at our disposal that will output one and only one result from a hypotheses set \(\{H_i\}_{i}\), which is also a partition of the sample space, denoting whether the item is classified into state \(j\). Let the observed outcome / testing result be \(H_j\). To find the probability that a new observation is of label \(j\), given that the classifier says it was, we combining the formula given above and arrive at

\[

\mathbb{P}(S_j | H_j) = \frac{

\mathbb{P}(H_j | S_j) \mathbb{P}(S_j)

}{

\mathbb{P}(H_j)

} = \frac{

\mathbb{P}(H_j | S_j) \mathbb{P}(S_j)

}{

\sum_i \mathbb{P}(H_j | S_i) \mathbb{P}(S_i)

}

\]

Let’s interpret this result:

- We need to know the prevalence of each possible label \(\mathbb{P}(S_i)\), a.k.a. base rate

- We need to know the performance of the classifier, denoted by \(\mathbb{P}(H_j | S_i)\), which can often be further decomposed into, at least, two types:

- Recall - \(\mathbb{P}(H_j | S_j)\): Given that the true label is \(j\), the probability that the classifier can correct predict

- False Discovery - \(\mathbb{P}(H_j | S_i), i \neq j\): Given that the true label is not \(j\), the probability that the classifier predict the item to be of label \(j\)

- For more information on this decomposition, one should read more about confusion matrix

- \(\mathbb{P}(S_j | H_j) \propto \mathbb{P}(S_j)\): Given additional data / evidence \(H_j\), we adjust our belief of prior unconditional information \(\mathbb{P}(S_j)\) with a multiplier \(\frac{ \mathbb{P}(H_j | S_j) }{ \sum_i \mathbb{P}(H_j | S_i) \mathbb{P}(S_i) }\).

Example

Two-Class Hard Classification

Without further due, let’s get back to the teaser question. Let \(Y\) denote the true label and \(\widehat{Y}\) denote the predicted label. Without loss of generality, we denote the two classes by 0 and 1 respectively. Since this is a two-class hard classification problem, \(Y, \widehat{Y} \in \{0, 1\}\). Therefore, applying the formula derived in the solution section, \[ \mathbb{P}(Y = 1 | \widehat{Y} = 1) = \frac{ \mathbb{P}(\widehat{Y} = 1 | Y = 1) \mathbb{P}(Y = 1) }{ \mathbb{P}(\widehat{Y} = 1 | Y = 1) \mathbb{P}(Y = 1) + \mathbb{P}(\widehat{Y} = 1 | Y = 0) \mathbb{P}(Y = 0) } \] From the problem statement, we know that

“population prevalence of 0’s is 90%”

- \(\mathbb{P}(Y = 0) = 90 \%\)

“population prevalence of 1’s is 10%”

- \(\mathbb{P}(Y = 1) = 10 \%\)

“recall of classifier is 90%”

- \(\mathbb{P}(\widehat{Y} = 1 | Y = 1) = 90 \%\)

“false discovery rate of classifier is 5%”

- \(\mathbb{P}(\widehat{Y} = 1 | Y = 0) = 5 \%\)

Therefore, plugging the numbers into the equation, we determine that the precision of the classifier is \[ \mathbb{P}(Y = 1 | \widehat{Y} = 1) = \frac{ (90 \%)(10 \%) }{ (90 \%)(10 \%) + (5 \%)(90 \%) } = \frac{2}{3} \approx 66.67 \% \] which is OK but not that impressive despite the high recall and low false discovery rate.

Disease Diagnosis

Sometimes the probabilities are not directly given in the problem statement, but instead, a confusion matrix is provided. As a result, one will need to estimate the proportions from data. Such examples are often given in a setting of epidemiological study or fraud detection. Consider a case of rare disease where only 1% of the population is infected. We conduct a controlled lab experiment with results shown below.

| Number of People | Infected | Healthy | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Test Positive | 50 | 20 | 70 |

| Test Negative | 15 | 35 | 50 |

| Total | 65 | 55 | 120 |

Connecting with the first example, the medical testing procedure here can be considered as a classifier.

“1% of the population is infected”

- Prevalence of infected population: \(\widehat{\mathbb{P}}(Y = 1) = 1 \%\)

- Prevalence of healthy population: \(\widehat{\mathbb{P}}(Y = 0) = 1 - \widehat{\mathbb{P}}(Y = 1) = 99 \%\)

Next, we derive the performance of out testing procedure from the confusion matrix.

- Recall is given by

\[ \widehat{\mathbb{P}}(\widehat{Y} = 1 | Y = 1) = \frac{ \# \text{Infected Subjects Tested Positive} }{ \# \text{Infected} } = \frac{50}{65} = \frac{10}{13} \approx 76.92 \% \] - False discovery rate is given by \[ \widehat{\mathbb{P}}(\widehat{Y} = 1 | Y = 0) = \frac{ \# \text{Healthy Subjects Tested Positive} }{ \# \text{Healthy} } = \frac{20}{55} = \frac{2}{11} \approx 18.18 \% \]

Therefore, the estimated precision of this testing procedure is

Base Rate Fallacy

Many people have a hard time digest the above disappointing result. Both recall and false discovery rate seem to be reasonable, but the resulting precision is terrible. Such a fallacy, commonly known as base rate fallacy, is well explained by Wikipedia

If presented with related base rate information (i.e. generic, general information) and specific information (information pertaining only to a certain case), the mind tends to ignore the former and focus on the latter.

Let’s first look at the main equation we having been leveraging so far mathematically, and then I will provide a frequentist’s interpretation of this phenomenon which I found more concrete and easier to swallow than Bayesian view of adjusting beliefs.

One way to rewrite precision \(\mathbb{P}(Y = 1 | \widehat{Y} = 1)\) is to connect it with odds ratios, \[ \mathbb{P}(Y = 1 | \widehat{Y} = 1) = \frac{ 1 }{ 1 + \frac{ \mathbb{P}(\widehat{Y} = 1 | Y = 0) }{ \mathbb{P}(\widehat{Y} = 1 | Y = 1) } \cdot \frac{ \mathbb{P}(Y = 0) }{ \mathbb{P}(Y = 1) } } \] We can see that the absolute magnitude of precision will be low if the product of odds ratios is large. In a low-incidence population, \(\frac{ \mathbb{P}(Y = 0) }{ \mathbb{P}(Y = 1) } = \frac{ \mathbb{P}(Y = 0) }{ 1 - \mathbb{P}(Y = 0) }\) can be very high, hence driving down the precision in an absolute sense.

Another way to look at precision \(\mathbb{P}(Y = 1 | \widehat{Y} = 1)\) is to connect with the base rate \(\mathbb{P}(Y = 1)\), \[ \mathbb{P}(Y = 1 | \widehat{Y} = 1) = \frac{ 1 }{ 1 + \bigg( \frac{ \mathbb{P}(\widehat{Y} = 1 | Y = 0) }{ \mathbb{P}(\widehat{Y} = 1 | Y = 1) } - 1 \bigg) \cdot \mathbb{P}(Y = 0) } \cdot \mathbb{P}(Y = 1) \] It is obvious to see that the precision is proportional to base rate \(\mathbb{P}(Y = 1)\) and the informational update of our belief is governed by the multiplier. For a given population, the prevalence \(\mathbb{P}(Y = 0)\) and \(\mathbb{P}(Y = 1)\) are fixed. In order to increase the multiplier, we need a very low odds ratio of \(\frac{ \mathbb{P}(\widehat{Y} = 1 | Y = 0) }{ \mathbb{P}(\widehat{Y} = 1 | Y = 1) }\), which means we need low false discovery and high recall. However, even the multiplier is large, the final result is always anchored by the base rate which is why precision is generally low for the rare disease case.

As we alluded to earlier, all formula covered in this post are true in probability theory regardless of frequentist or Bayesian interpretation. A frequentist’s view, however, can be more concrete in this case. We will interpret probability as long-run average of sample proportion and reconcile the tension between general versus specific information.

- \(\mathbb{P}(Y = 1)\): If one randomly sample from a large population, the proportion that the selected subject is infected

- \(\mathbb{P}(\widehat{Y} = 1 | Y = 1)\): For a given infected subject, if one repeats the testing procedure many times, the proportion that the testing results show as positive

- \(\mathbb{P}(Y = 1 | \widehat{Y} = 1)\): Among a large sample of subjects with positive test results, the proportion that is truly infected

Now the question is, as a patient receiving such a test, which quantity should you care about?

- \(\mathbb{P}(Y = 1)\): This is about the population, or general phenomenon, but not about the specific patient

- \(\mathbb{P}(\widehat{Y} = 1 | Y = 1)\): This is about the medical testing procedure. It is a proxy or indicator, but does not directly measure ones specific risk

- \(\mathbb{P}(Y = 1 | \widehat{Y} = 1)\): This is the relevant quantity for an individual whose test result is positive because it directly reflects the likelihood, controlled for population prevalence, that one is infected

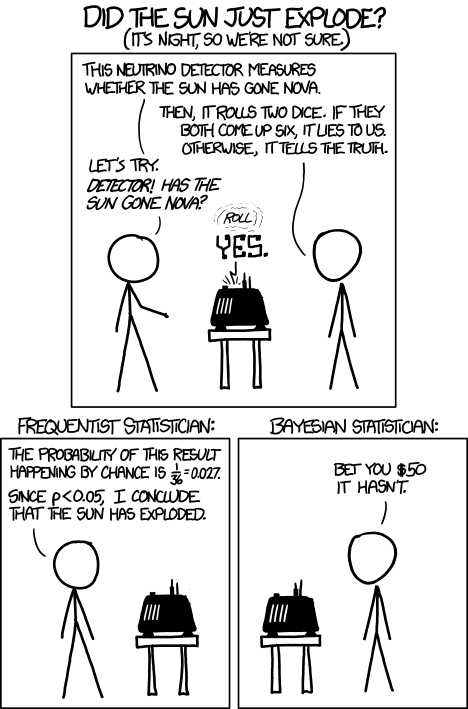

xkcd cartoon.

Figure 1: Frequentists vs. Bayesians

Key Takeaway

With given characteristics (recall and false discovery rate) of a classifier, its precision evaluated on a randomly chosen new sample depends on the population base rate.

We present an animated contour plot below to hammer this concept. One should focus on

- The area of high precision region increases as the base rate of incidence increases

- The lower right corner (i.e. high recall and low false discovery rate) is where practical scenarios typically reside

Exercise

After reading this post, one should be able to apply the formula to flip conditional probabilities and determine commonly asked measures such as precision of a classifier. At the end, we present another example as an exercise.

You just joined a cool startup that offers free lunch at work 25% of the time at random. One day, you wake up late and feel really hungry. You wonder if there is “breakfast” (actually, lunch) at work. Therefore, you call your buddy who is already at the office, and he tells you that there is free lunch. However, you know from past experience that he lies to you roughly a third of the time. What is the probability that there indeed is free lunch at work for the day?

Hint: In this case, whether there is free lunch is the parameter of interest, and your buddy’s response is the classifier. You want to determine its precision.

Answer: \(\frac{2}{5} = 40 \%\).