When working with data you must:

Figure out what you want to do.

Describe those tasks in the form of a computer program.

Execute the program.

The dplyr package makes these steps fast and easy:

By constraining your options, it helps you think about your data manipulation challenges.

It provides simple “verbs”, functions that correspond to the most common data manipulation tasks, to help you translate your thoughts into code.

It uses efficient backends, so you spend less time waiting for the computer.

This document introduces you to dplyr’s basic set of tools, and shows you how to apply them to data frames. dplyr also supports databases via the dbplyr package, once you’ve installed, read vignette("dbplyr") to learn more.

Data: nycflights13

To explore the basic data manipulation verbs of dplyr, we’ll use nycflights13::flights. This dataset contains all 336776 flights that departed from New York City in 2013. The data comes from the US Bureau of Transportation Statistics, and is documented in ?nycflights13

library(nycflights13)

dim(flights)

#> [1] 336776 19

flights

#> # A tibble: 336,776 x 19

#> year month day dep_time sched_dep_time dep_delay arr_time sched_arr_time

#> <int> <int> <int> <int> <int> <dbl> <int> <int>

#> 1 2013 1 1 517 515 2 830 819

#> 2 2013 1 1 533 529 4 850 830

#> 3 2013 1 1 542 540 2 923 850

#> 4 2013 1 1 544 545 -1 1004 1022

#> # … with 336,772 more rows, and 11 more variables: arr_delay <dbl>,

#> # carrier <chr>, flight <int>, tailnum <chr>, origin <chr>, dest <chr>,

#> # air_time <dbl>, distance <dbl>, hour <dbl>, minute <dbl>, time_hour <dttm>Note that nycflights13::flights is a tibble, a modern reimagining of the data frame. It’s particularly useful for large datasets because it only prints the first few rows. You can learn more about tibbles at http://tibble.tidyverse.org; in particular you can convert data frames to tibbles with as_tibble().

Single table verbs

Dplyr aims to provide a function for each basic verb of data manipulation:

-

filter()to select cases based on their values. -

arrange()to reorder the cases. -

select()andrename()to select variables based on their names. -

mutate()andtransmute()to add new variables that are functions of existing variables. -

summarise()to condense multiple values to a single value. -

sample_n()andsample_frac()to take random samples.

Filter rows with filter()

filter() allows you to select a subset of rows in a data frame. Like all single verbs, the first argument is the tibble (or data frame). The second and subsequent arguments refer to variables within that data frame, selecting rows where the expression is TRUE.

For example, we can select all flights on January 1st with:

filter(flights, month == 1, day == 1)

#> # A tibble: 842 x 19

#> year month day dep_time sched_dep_time dep_delay arr_time sched_arr_time

#> <int> <int> <int> <int> <int> <dbl> <int> <int>

#> 1 2013 1 1 517 515 2 830 819

#> 2 2013 1 1 533 529 4 850 830

#> 3 2013 1 1 542 540 2 923 850

#> 4 2013 1 1 544 545 -1 1004 1022

#> # … with 838 more rows, and 11 more variables: arr_delay <dbl>, carrier <chr>,

#> # flight <int>, tailnum <chr>, origin <chr>, dest <chr>, air_time <dbl>,

#> # distance <dbl>, hour <dbl>, minute <dbl>, time_hour <dttm>This is rougly equivalent to this base R code:

Arrange rows with arrange()

arrange() works similarly to filter() except that instead of filtering or selecting rows, it reorders them. It takes a data frame, and a set of column names (or more complicated expressions) to order by. If you provide more than one column name, each additional column will be used to break ties in the values of preceding columns:

arrange(flights, year, month, day)

#> # A tibble: 336,776 x 19

#> year month day dep_time sched_dep_time dep_delay arr_time sched_arr_time

#> <int> <int> <int> <int> <int> <dbl> <int> <int>

#> 1 2013 1 1 517 515 2 830 819

#> 2 2013 1 1 533 529 4 850 830

#> 3 2013 1 1 542 540 2 923 850

#> 4 2013 1 1 544 545 -1 1004 1022

#> # … with 336,772 more rows, and 11 more variables: arr_delay <dbl>,

#> # carrier <chr>, flight <int>, tailnum <chr>, origin <chr>, dest <chr>,

#> # air_time <dbl>, distance <dbl>, hour <dbl>, minute <dbl>, time_hour <dttm>Use desc() to order a column in descending order:

arrange(flights, desc(arr_delay))

#> # A tibble: 336,776 x 19

#> year month day dep_time sched_dep_time dep_delay arr_time sched_arr_time

#> <int> <int> <int> <int> <int> <dbl> <int> <int>

#> 1 2013 1 9 641 900 1301 1242 1530

#> 2 2013 6 15 1432 1935 1137 1607 2120

#> 3 2013 1 10 1121 1635 1126 1239 1810

#> 4 2013 9 20 1139 1845 1014 1457 2210

#> # … with 336,772 more rows, and 11 more variables: arr_delay <dbl>,

#> # carrier <chr>, flight <int>, tailnum <chr>, origin <chr>, dest <chr>,

#> # air_time <dbl>, distance <dbl>, hour <dbl>, minute <dbl>, time_hour <dttm>

Select columns with select()

Often you work with large datasets with many columns but only a few are actually of interest to you. select() allows you to rapidly zoom in on a useful subset using operations that usually only work on numeric variable positions:

# Select columns by name

select(flights, year, month, day)

#> # A tibble: 336,776 x 3

#> year month day

#> <int> <int> <int>

#> 1 2013 1 1

#> 2 2013 1 1

#> 3 2013 1 1

#> 4 2013 1 1

#> # … with 336,772 more rows

# Select all columns between year and day (inclusive)

select(flights, year:day)

#> # A tibble: 336,776 x 3

#> year month day

#> <int> <int> <int>

#> 1 2013 1 1

#> 2 2013 1 1

#> 3 2013 1 1

#> 4 2013 1 1

#> # … with 336,772 more rows

# Select all columns except those from year to day (inclusive)

select(flights, -(year:day))

#> # A tibble: 336,776 x 16

#> dep_time sched_dep_time dep_delay arr_time sched_arr_time arr_delay carrier

#> <int> <int> <dbl> <int> <int> <dbl> <chr>

#> 1 517 515 2 830 819 11 UA

#> 2 533 529 4 850 830 20 UA

#> 3 542 540 2 923 850 33 AA

#> 4 544 545 -1 1004 1022 -18 B6

#> # … with 336,772 more rows, and 9 more variables: flight <int>, tailnum <chr>,

#> # origin <chr>, dest <chr>, air_time <dbl>, distance <dbl>, hour <dbl>,

#> # minute <dbl>, time_hour <dttm>There are a number of helper functions you can use within select(), like starts_with(), ends_with(), matches() and contains(). These let you quickly match larger blocks of variables that meet some criterion. See ?select for more details.

You can rename variables with select() by using named arguments:

select(flights, tail_num = tailnum)

#> # A tibble: 336,776 x 1

#> tail_num

#> <chr>

#> 1 N14228

#> 2 N24211

#> 3 N619AA

#> 4 N804JB

#> # … with 336,772 more rowsBut because select() drops all the variables not explicitly mentioned, it’s not that useful. Instead, use rename():

rename(flights, tail_num = tailnum)

#> # A tibble: 336,776 x 19

#> year month day dep_time sched_dep_time dep_delay arr_time sched_arr_time

#> <int> <int> <int> <int> <int> <dbl> <int> <int>

#> 1 2013 1 1 517 515 2 830 819

#> 2 2013 1 1 533 529 4 850 830

#> 3 2013 1 1 542 540 2 923 850

#> 4 2013 1 1 544 545 -1 1004 1022

#> # … with 336,772 more rows, and 11 more variables: arr_delay <dbl>,

#> # carrier <chr>, flight <int>, tail_num <chr>, origin <chr>, dest <chr>,

#> # air_time <dbl>, distance <dbl>, hour <dbl>, minute <dbl>, time_hour <dttm>

Add new columns with mutate()

Besides selecting sets of existing columns, it’s often useful to add new columns that are functions of existing columns. This is the job of mutate():

mutate(flights,

gain = arr_delay - dep_delay,

speed = distance / air_time * 60

)

#> # A tibble: 336,776 x 21

#> year month day dep_time sched_dep_time dep_delay arr_time sched_arr_time

#> <int> <int> <int> <int> <int> <dbl> <int> <int>

#> 1 2013 1 1 517 515 2 830 819

#> 2 2013 1 1 533 529 4 850 830

#> 3 2013 1 1 542 540 2 923 850

#> 4 2013 1 1 544 545 -1 1004 1022

#> # … with 336,772 more rows, and 13 more variables: arr_delay <dbl>,

#> # carrier <chr>, flight <int>, tailnum <chr>, origin <chr>, dest <chr>,

#> # air_time <dbl>, distance <dbl>, hour <dbl>, minute <dbl>, time_hour <dttm>,

#> # gain <dbl>, speed <dbl>dplyr::mutate() is similar to the base transform(), but allows you to refer to columns that you’ve just created:

mutate(flights,

gain = arr_delay - dep_delay,

gain_per_hour = gain / (air_time / 60)

)

#> # A tibble: 336,776 x 21

#> year month day dep_time sched_dep_time dep_delay arr_time sched_arr_time

#> <int> <int> <int> <int> <int> <dbl> <int> <int>

#> 1 2013 1 1 517 515 2 830 819

#> 2 2013 1 1 533 529 4 850 830

#> 3 2013 1 1 542 540 2 923 850

#> 4 2013 1 1 544 545 -1 1004 1022

#> # … with 336,772 more rows, and 13 more variables: arr_delay <dbl>,

#> # carrier <chr>, flight <int>, tailnum <chr>, origin <chr>, dest <chr>,

#> # air_time <dbl>, distance <dbl>, hour <dbl>, minute <dbl>, time_hour <dttm>,

#> # gain <dbl>, gain_per_hour <dbl>If you only want to keep the new variables, use transmute():

Summarise values with summarise()

The last verb is summarise(). It collapses a data frame to a single row.

summarise(flights,

delay = mean(dep_delay, na.rm = TRUE)

)

#> # A tibble: 1 x 1

#> delay

#> <dbl>

#> 1 12.6It’s not that useful until we learn the group_by() verb below.

Randomly sample rows with sample_n() and sample_frac()

You can use sample_n() and sample_frac() to take a random sample of rows: use sample_n() for a fixed number and sample_frac() for a fixed fraction.

sample_n(flights, 10)

#> # A tibble: 10 x 19

#> year month day dep_time sched_dep_time dep_delay arr_time sched_arr_time

#> <int> <int> <int> <int> <int> <dbl> <int> <int>

#> 1 2013 9 9 1440 1429 11 1649 1655

#> 2 2013 5 15 1427 1429 -2 1728 1738

#> 3 2013 8 14 1121 1120 1 1228 1233

#> 4 2013 8 4 1448 1429 19 1657 1659

#> # … with 6 more rows, and 11 more variables: arr_delay <dbl>, carrier <chr>,

#> # flight <int>, tailnum <chr>, origin <chr>, dest <chr>, air_time <dbl>,

#> # distance <dbl>, hour <dbl>, minute <dbl>, time_hour <dttm>

sample_frac(flights, 0.01)

#> # A tibble: 3,368 x 19

#> year month day dep_time sched_dep_time dep_delay arr_time sched_arr_time

#> <int> <int> <int> <int> <int> <dbl> <int> <int>

#> 1 2013 11 7 1855 1900 -5 2238 2251

#> 2 2013 3 10 1930 1935 -5 2213 2242

#> 3 2013 2 22 1622 1615 7 1820 1831

#> 4 2013 8 9 602 605 -3 744 749

#> # … with 3,364 more rows, and 11 more variables: arr_delay <dbl>,

#> # carrier <chr>, flight <int>, tailnum <chr>, origin <chr>, dest <chr>,

#> # air_time <dbl>, distance <dbl>, hour <dbl>, minute <dbl>, time_hour <dttm>Use replace = TRUE to perform a bootstrap sample. If needed, you can weight the sample with the weight argument.

Commonalities

You may have noticed that the syntax and function of all these verbs are very similar:

The first argument is a data frame.

The subsequent arguments describe what to do with the data frame. You can refer to columns in the data frame directly without using

$.The result is a new data frame

Together these properties make it easy to chain together multiple simple steps to achieve a complex result.

These five functions provide the basis of a language of data manipulation. At the most basic level, you can only alter a tidy data frame in five useful ways: you can reorder the rows (arrange()), pick observations and variables of interest (filter() and select()), add new variables that are functions of existing variables (mutate()), or collapse many values to a summary (summarise()). The remainder of the language comes from applying the five functions to different types of data. For example, I’ll discuss how these functions work with grouped data.

Patterns of operations

The dplyr verbs can be classified by the type of operations they accomplish (we sometimes speak of their semantics, i.e., their meaning). The most important and useful distinction is between grouped and ungrouped operations. In addition, it is helpful to have a good grasp of the difference between select and mutate operations.

Grouped operations

The dplyr verbs are useful on their own, but they become even more powerful when you apply them to groups of observations within a dataset. In dplyr, you do this with the group_by() function. It breaks down a dataset into specified groups of rows. When you then apply the verbs above on the resulting object they’ll be automatically applied “by group”.

Grouping affects the verbs as follows:

grouped

select()is the same as ungroupedselect(), except that grouping variables are always retained.grouped

arrange()is the same as ungrouped; unless you set.by_group = TRUE, in which case it orders first by the grouping variablesmutate()andfilter()are most useful in conjunction with window functions (likerank(), ormin(x) == x). They are described in detail invignette("window-functions").sample_n()andsample_frac()sample the specified number/fraction of rows in each group.summarise()computes the summary for each group.

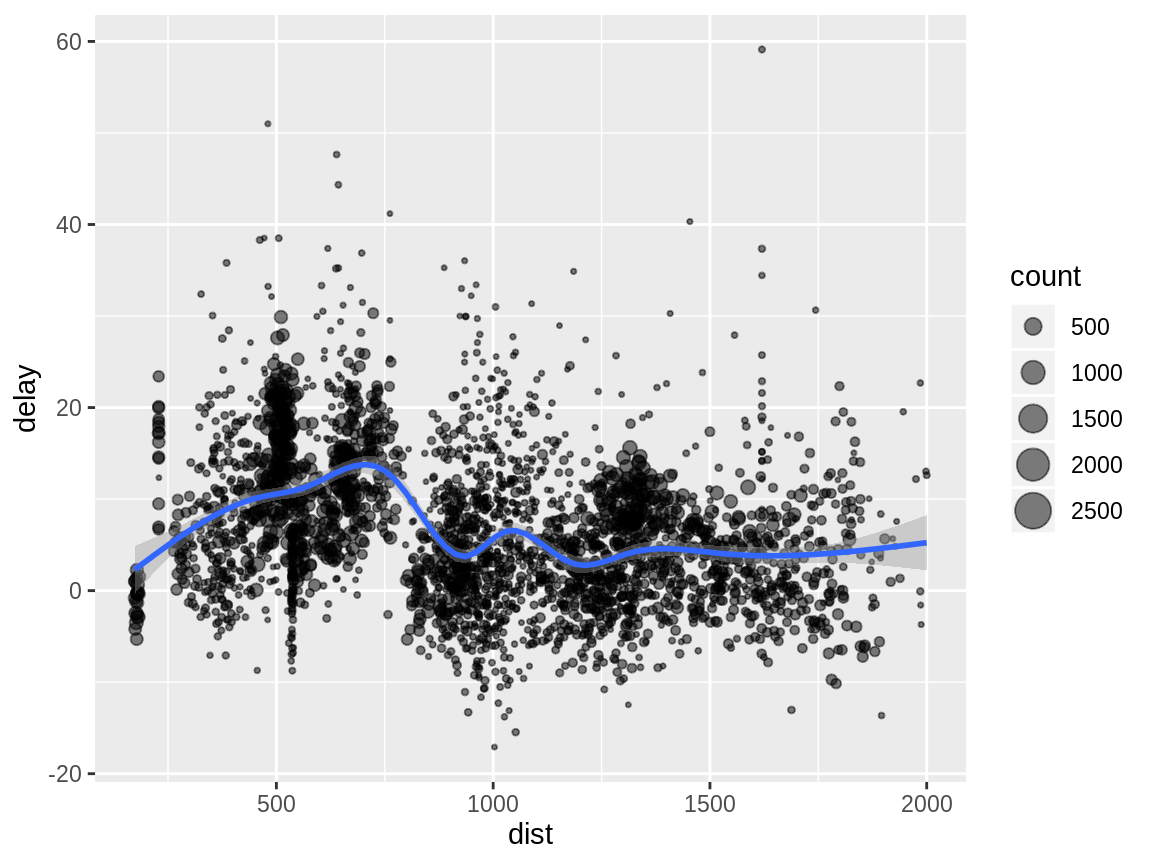

In the following example, we split the complete dataset into individual planes and then summarise each plane by counting the number of flights (count = n()) and computing the average distance (dist = mean(distance, na.rm = TRUE)) and arrival delay (delay = mean(arr_delay, na.rm = TRUE)). We then use ggplot2 to display the output.

by_tailnum <- group_by(flights, tailnum)

delay <- summarise(by_tailnum,

count = n(),

dist = mean(distance, na.rm = TRUE),

delay = mean(arr_delay, na.rm = TRUE))

delay <- filter(delay, count > 20, dist < 2000)

# Interestingly, the average delay is only slightly related to the

# average distance flown by a plane.

ggplot(delay, aes(dist, delay)) +

geom_point(aes(size = count), alpha = 1/2) +

geom_smooth() +

scale_size_area()

You use summarise() with aggregate functions, which take a vector of values and return a single number. There are many useful examples of such functions in base R like min(), max(), mean(), sum(), sd(), median(), and IQR(). dplyr provides a handful of others:

n(): the number of observations in the current groupn_distinct(x):the number of unique values inx.first(x),last(x)andnth(x, n)- these work similarly tox[1],x[length(x)], andx[n]but give you more control over the result if the value is missing.

For example, we could use these to find the number of planes and the number of flights that go to each possible destination:

destinations <- group_by(flights, dest)

summarise(destinations,

planes = n_distinct(tailnum),

flights = n()

)

#> # A tibble: 105 x 3

#> dest planes flights

#> <chr> <int> <int>

#> 1 ABQ 108 254

#> 2 ACK 58 265

#> 3 ALB 172 439

#> 4 ANC 6 8

#> # … with 101 more rowsWhen you group by multiple variables, each summary peels off one level of the grouping. That makes it easy to progressively roll-up a dataset:

daily <- group_by(flights, year, month, day)

(per_day <- summarise(daily, flights = n()))

#> # A tibble: 365 x 4

#> # Groups: year, month [12]

#> year month day flights

#> <int> <int> <int> <int>

#> 1 2013 1 1 842

#> 2 2013 1 2 943

#> 3 2013 1 3 914

#> 4 2013 1 4 915

#> # … with 361 more rows

(per_month <- summarise(per_day, flights = sum(flights)))

#> # A tibble: 12 x 3

#> # Groups: year [1]

#> year month flights

#> <int> <int> <int>

#> 1 2013 1 27004

#> 2 2013 2 24951

#> 3 2013 3 28834

#> 4 2013 4 28330

#> # … with 8 more rows

(per_year <- summarise(per_month, flights = sum(flights)))

#> # A tibble: 1 x 2

#> year flights

#> <int> <int>

#> 1 2013 336776However you need to be careful when progressively rolling up summaries like this: it’s ok for sums and counts, but you need to think about weighting for means and variances (it’s not possible to do this exactly for medians).

Selecting operations

One of the appealing features of dplyr is that you can refer to columns from the tibble as if they were regular variables. However, the syntactic uniformity of referring to bare column names hides semantical differences across the verbs. A column symbol supplied to select() does not have the same meaning as the same symbol supplied to mutate().

Selecting operations expect column names and positions. Hence, when you call select() with bare variable names, they actually represent their own positions in the tibble. The following calls are completely equivalent from dplyr’s point of view:

# `year` represents the integer 1

select(flights, year)

#> # A tibble: 336,776 x 1

#> year

#> <int>

#> 1 2013

#> 2 2013

#> 3 2013

#> 4 2013

#> # … with 336,772 more rows

select(flights, 1)

#> # A tibble: 336,776 x 1

#> year

#> <int>

#> 1 2013

#> 2 2013

#> 3 2013

#> 4 2013

#> # … with 336,772 more rowsBy the same token, this means that you cannot refer to variables from the surrounding context if they have the same name as one of the columns. In the following example, year still represents 1, not 5:

One useful subtlety is that this only applies to bare names and to selecting calls like c(year, month, day) or year:day. In all other cases, the columns of the data frame are not put in scope. This allows you to refer to contextual variables in selection helpers:

year <- "dep"

select(flights, starts_with(year))

#> # A tibble: 336,776 x 2

#> dep_time dep_delay

#> <int> <dbl>

#> 1 517 2

#> 2 533 4

#> 3 542 2

#> 4 544 -1

#> # … with 336,772 more rowsThese semantics are usually intuitive. But note the subtle difference:

year <- 5

select(flights, year, identity(year))

#> # A tibble: 336,776 x 2

#> year sched_dep_time

#> <int> <int>

#> 1 2013 515

#> 2 2013 529

#> 3 2013 540

#> 4 2013 545

#> # … with 336,772 more rowsIn the first argument, year represents its own position 1. In the second argument, year is evaluated in the surrounding context and represents the fifth column.

For a long time, select() used to only understand column positions. Counting from dplyr 0.6, it now understands column names as well. This makes it a bit easier to program with select():

vars <- c("year", "month")

select(flights, vars, "day")

#> # A tibble: 336,776 x 3

#> year month day

#> <int> <int> <int>

#> 1 2013 1 1

#> 2 2013 1 1

#> 3 2013 1 1

#> 4 2013 1 1

#> # … with 336,772 more rowsNote that the code above is somewhat unsafe because you might have added a column named vars to the tibble, or you might apply the code to another data frame containing such a column. To avoid this issue, you can wrap the variable in an identity() call as we mentioned above, as this will bypass column names. However, a more explicit and general method that works in all dplyr verbs is to unquote the variable with the !! operator. This tells dplyr to bypass the data frame and to directly look in the context:

# Let's create a new `vars` column:

flights$vars <- flights$year

# The new column won't be an issue if you evaluate `vars` in the

# context with the `!!` operator:

vars <- c("year", "month", "day")

select(flights, !! vars)

#> # A tibble: 336,776 x 3

#> year month day

#> <int> <int> <int>

#> 1 2013 1 1

#> 2 2013 1 1

#> 3 2013 1 1

#> 4 2013 1 1

#> # … with 336,772 more rowsThis operator is very useful when you need to use dplyr within custom functions. You can learn more about it in vignette("programming"). However it is important to understand the semantics of the verbs you are unquoting into, that is, the values they understand. As we have just seen, select() supports names and positions of columns. But that won’t be the case in other verbs like mutate() because they have different semantics.

Mutating operations

Mutate semantics are quite different from selection semantics. Whereas select() expects column names or positions, mutate() expects column vectors. Let’s create a smaller tibble for clarity:

When we use select(), the bare column names stand for ther own positions in the tibble. For mutate() on the other hand, column symbols represent the actual column vectors stored in the tibble. Consider what happens if we give a string or a number to mutate():

mutate(df, "year", 2)

#> # A tibble: 336,776 x 6

#> year month day dep_time `"year"` `2`

#> <int> <int> <int> <int> <chr> <dbl>

#> 1 2013 1 1 517 year 2

#> 2 2013 1 1 533 year 2

#> 3 2013 1 1 542 year 2

#> 4 2013 1 1 544 year 2

#> # … with 336,772 more rowsmutate() gets length-1 vectors that it interprets as new columns in the data frame. These vectors are recycled so they match the number of rows. That’s why it doesn’t make sense to supply expressions like "year" + 10 to mutate(). This amounts to adding 10 to a string! The correct expression is:

mutate(df, year + 10)

#> # A tibble: 336,776 x 5

#> year month day dep_time `year + 10`

#> <int> <int> <int> <int> <dbl>

#> 1 2013 1 1 517 2023

#> 2 2013 1 1 533 2023

#> 3 2013 1 1 542 2023

#> 4 2013 1 1 544 2023

#> # … with 336,772 more rowsIn the same way, you can unquote values from the context if these values represent a valid column. They must be either length 1 (they then get recycled) or have the same length as the number of rows. In the following example we create a new vector that we add to the data frame:

var <- seq(1, nrow(df))

mutate(df, new = var)

#> # A tibble: 336,776 x 5

#> year month day dep_time new

#> <int> <int> <int> <int> <int>

#> 1 2013 1 1 517 1

#> 2 2013 1 1 533 2

#> 3 2013 1 1 542 3

#> 4 2013 1 1 544 4

#> # … with 336,772 more rowsA case in point is group_by(). While you might think it has select semantics, it actually has mutate semantics. This is quite handy as it allows to group by a modified column:

group_by(df, month)

#> # A tibble: 336,776 x 4

#> # Groups: month [12]

#> year month day dep_time

#> <int> <int> <int> <int>

#> 1 2013 1 1 517

#> 2 2013 1 1 533

#> 3 2013 1 1 542

#> 4 2013 1 1 544

#> # … with 336,772 more rows

group_by(df, month = as.factor(month))

#> # A tibble: 336,776 x 4

#> # Groups: month [12]

#> year month day dep_time

#> <int> <fct> <int> <int>

#> 1 2013 1 1 517

#> 2 2013 1 1 533

#> 3 2013 1 1 542

#> 4 2013 1 1 544

#> # … with 336,772 more rows

group_by(df, day_binned = cut(day, 3))

#> # A tibble: 336,776 x 5

#> # Groups: day_binned [3]

#> year month day dep_time day_binned

#> <int> <int> <int> <int> <fct>

#> 1 2013 1 1 517 (0.97,11]

#> 2 2013 1 1 533 (0.97,11]

#> 3 2013 1 1 542 (0.97,11]

#> 4 2013 1 1 544 (0.97,11]

#> # … with 336,772 more rowsThis is why you can’t supply a column name to group_by(). This amounts to creating a new column containing the string recycled to the number of rows:

group_by(df, "month")

#> # A tibble: 336,776 x 5

#> # Groups: "month" [1]

#> year month day dep_time `"month"`

#> <int> <int> <int> <int> <chr>

#> 1 2013 1 1 517 month

#> 2 2013 1 1 533 month

#> 3 2013 1 1 542 month

#> 4 2013 1 1 544 month

#> # … with 336,772 more rowsSince grouping with select semantics can be sometimes useful as well, we have added the group_by_at() variant. In dplyr, variants suffixed with _at() support selection semantics in their second argument. You just need to wrap the selection with vars():

group_by_at(df, vars(year:day))

#> # A tibble: 336,776 x 4

#> # Groups: year, month, day [365]

#> year month day dep_time

#> <int> <int> <int> <int>

#> 1 2013 1 1 517

#> 2 2013 1 1 533

#> 3 2013 1 1 542

#> 4 2013 1 1 544

#> # … with 336,772 more rowsYou can read more about the _at() and _if() variants in the ?scoped help page.

Piping

The dplyr API is functional in the sense that function calls don’t have side-effects. You must always save their results. This doesn’t lead to particularly elegant code, especially if you want to do many operations at once. You either have to do it step-by-step:

a1 <- group_by(flights, year, month, day)

a2 <- select(a1, arr_delay, dep_delay)

a3 <- summarise(a2,

arr = mean(arr_delay, na.rm = TRUE),

dep = mean(dep_delay, na.rm = TRUE))

a4 <- filter(a3, arr > 30 | dep > 30)Or if you don’t want to name the intermediate results, you need to wrap the function calls inside each other:

filter(

summarise(

select(

group_by(flights, year, month, day),

arr_delay, dep_delay

),

arr = mean(arr_delay, na.rm = TRUE),

dep = mean(dep_delay, na.rm = TRUE)

),

arr > 30 | dep > 30

)

#> Adding missing grouping variables: `year`, `month`, `day`

#> # A tibble: 49 x 5

#> # Groups: year, month [11]

#> year month day arr dep

#> <int> <int> <int> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 2013 1 16 34.2 24.6

#> 2 2013 1 31 32.6 28.7

#> 3 2013 2 11 36.3 39.1

#> 4 2013 2 27 31.3 37.8

#> # … with 45 more rowsThis is difficult to read because the order of the operations is from inside to out. Thus, the arguments are a long way away from the function. To get around this problem, dplyr provides the %>% operator from magrittr. x %>% f(y) turns into f(x, y) so you can use it to rewrite multiple operations that you can read left-to-right, top-to-bottom:

Other data sources

As well as data frames, dplyr works with data that is stored in other ways, like data tables, databases and multidimensional arrays.

Data table

dplyr also provides data table methods for all verbs through dtplyr. If you’re using data.tables already this lets you to use dplyr syntax for data manipulation, and data.table for everything else.

For multiple operations, data.table can be faster because you usually use it with multiple verbs simultaneously. For example, with data table you can do a mutate and a select in a single step. It’s smart enough to know that there’s no point in computing the new variable for rows you’re about to throw away.

The advantages of using dplyr with data tables are:

For common data manipulation tasks, it insulates you from the reference semantics of data.tables, and protects you from accidentally modifying your data.

Instead of one complex method built on the subscripting operator (

[), it provides many simple methods.

Databases

dplyr also allows you to use the same verbs with a remote database. It takes care of generating the SQL for you so that you can avoid the cognitive challenge of constantly switching between languages. To use these capabilities, you’ll need to install the dbplyr package and then read vignette("dbplyr") for the details.

Multidimensional arrays / cubes

tbl_cube() provides an experimental interface to multidimensional arrays or data cubes. If you’re using this form of data in R, please get in touch so I can better understand your needs.

Comparisons

Compared to all existing options, dplyr:

abstracts away how your data is stored, so that you can work with data frames, data tables and remote databases using the same set of functions. This lets you focus on what you want to achieve, not on the logistics of data storage.

provides a thoughtful default

print()method that doesn’t automatically print pages of data to the screen (this was inspired by data table’s output).

Compared to base functions:

dplyr is much more consistent; functions have the same interface. So once you’ve mastered one, you can easily pick up the others

base functions tend to be based around vectors; dplyr is based around data frames

Compared to plyr, dplyr:

is much much faster

provides a better thought out set of joins

only provides tools for working with data frames (e.g. most of dplyr is equivalent to

ddply()+ various functions,do()is equivalent todlply())

Compared to virtual data frame approaches: